Achkal

Brick, the first manufactured building material that was produced over 3800 years ago continue to be in use and shape our built environment and has survived every social transition remaining relevant as a primary building material globally. Discovery of fire stabilising earth to become a water-resistant material was the basis, but the idea of making a single versatile module/unit that could be assembled in endless patterns and forms to produce walls, floors and roofs including domes and vaults, was revolutionary.

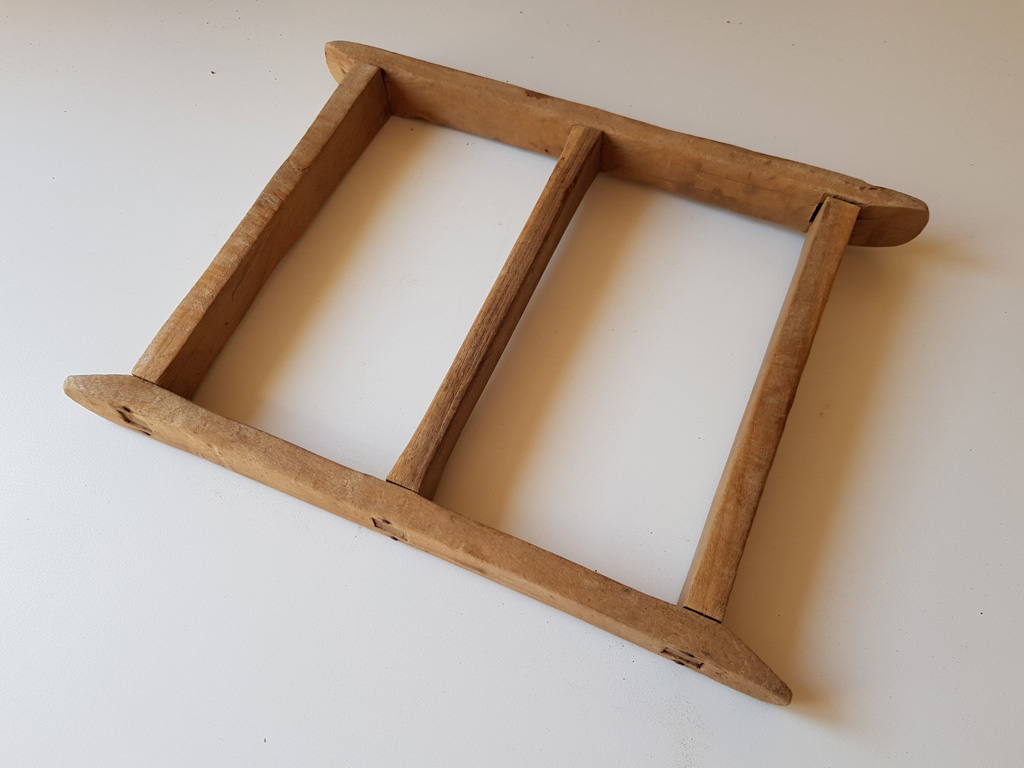

In preindustrial techniques, the size of the brick, enabled through wooden moulds for simply forming the units on an open field, was based on the human scale. A scoop of the volume of earth that could be held within the hands of the craftsman, resulted in light weight 1” high bricks were equally easy on the masons’ hands. These were fired in kiln structures that were the stack of bricks themselves and were fired with locally available thinning and branches from trees, or bio-waste.

Industrially produced bricks are sized for the convenience of the machine´s efficiency. They use optimum clay, sourced from huge quarries through machines, use fossil fuel and achieve higher strength at a higher economic cost, and an even higher environmental cost. We were taught to use these in architecture school based on British construction standards and looked down upon the weaker preindustrial local bricks that were not as perfect in their surfaces or as strong.

This piece reminds of my discovery that the bad brick was indeed the good brick. Stronger is not always better, or more humane. Often hand-crafted objects that engage the body and mind of the maker, is the more intelligent object, and above all it holds the life of the maker within it, and the human imprint. It causes us to reflect the role of machines and tools, and if the human is in control or if the tool has started controlling the human.

This brick mould is a perfectly solved object, of the kind that is still in use in rural Tamil Nadu and sits on my shelf as a benchmark to measure emerging new technologies.

Anupama Kundoo

Anupama Kundoo’s practice based in Pondicherry and Berlin, involves extensive material research to achieve high aesthetic and low environmental impact to achieve an architecture that is socio-economically beneficial. Kundoo, Professor at Potsdam School of Architecture Germany, graduated in 1989 from Mumbai and obtained her PhD from Berlin in 2008. Her work was exhibited twice at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2012 and 2016, and will be exhibited as a solo show at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark in 2020.